The Coolidge Tube – At a Glance

Electrogravitics began not in a lab, but in the imagination of a teenager fueled by science fiction. Townsend Brown, inspired by stories of futuristic travel, used a salvaged Coolidge X-ray machine in an experiment that led to a surprising discovery: capacitors could move under high voltage. This marked the first glimpse of what would later be called the Biefeld-Brown Effect. The Coolidge tube became a catalyst for years of research, patents, and debate about the relationship between electricity and gravity. Brown’s curiosity ignited a field still filled with unanswered questions and untapped potential.

Read time: 6 minutes

Introduction to The Coolidge Tube

What if one of the most curious scientific phenomena of the 20th century began not in a lab, but in the imagination of a teenager inspired by science fiction?

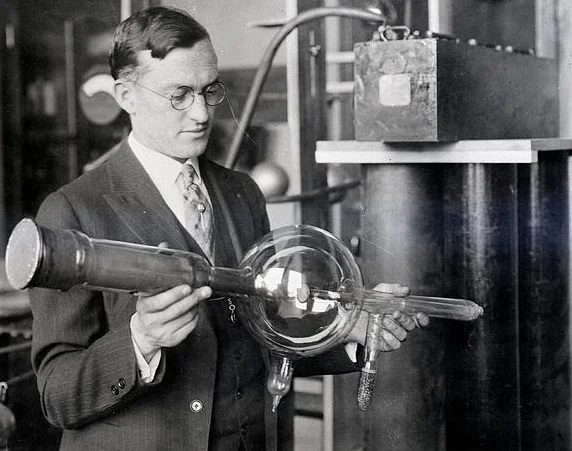

This is how the story of electrogravitics begins, with a young Townsend Brown, his head full of rockets and space travel, and a bold idea about using X-rays as a propulsion force. While testing that theory with a salvaged Coolidge X-ray machine, he observed something he didn’t expect. The Coolidge tube played a central role in that moment of discovery, and it changed everything.

Where Curiosity Meets Discovery

Townsend Brown, like many of his generation, grew up on the pages of Tom Swift and the scientific marvels of Jules Verne and H.G. Wells. These stories planted the seeds of possibility in his young mind. When the X-ray machine entered public knowledge, Brown speculated that perhaps X-rays could create thrust.

He convinced his parents to buy him an old Coolidge tube, and he mounted it on a balancing support, expecting motion from the tube itself. But it wasn’t the X-rays that moved anything; it was the wires.

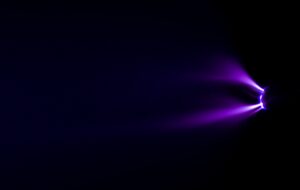

After examining the motion more closely, Brown discovered that the movement originated from a capacitor wired in series with the tube. He rewired the system and mounted only the capacitor on the balancing support. When powered again, the capacitor moved. This marked Brown’s first documented observation of what would eventually be known as the Biefeld-Brown Effect.

After the Coolidge Tube: The Experiments That Moved

Over the next several years, Brown refined his capacitor designs. His observations culminated in British Patent No. 300,311, which described several experiments supporting the electrogravitic effect.

In one, Brown used nine lead plates separated by insulators made from empire cloth soaked in mineral oil and paraffin, then sealed in shellac and finished with Bakelite. Two of these capacitors were mounted on a beam with a center bearing. When powered, they turned.

To rule out ion wind, Brown submerged the capacitors in mineral oil and applied 300,000 volts. The motion persisted. He also tested a vacuum tube version and suspended lead balls at long distances to observe further effects. The Coolidge tube remained a foundational reference point for understanding how high-voltage systems might influence motion.

Each test reinforced his claim that a force could be generated through high-voltage interactions between capacitive materials, potentially bridging electromagnetism and gravity.

The Bigger Possibility

Brown’s conclusions met skepticism from mainstream scientists. Yet, he preserved his work carefully in his first patent, a document that continues to spark interest in modern-day physicists and researchers.

Today, as we rethink how we power motion and explore advanced propulsion systems, Brown’s early insights invite renewed attention. If even part of his discovery proves scalable, it could reshape the future of transportation, aerospace, and energy systems. The Coolidge tube, which helped launch his earliest experiments, remains a symbol of that untapped potential.

“Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited, whereas imagination embraces the entire world, stimulating progress, giving birth to evolution.” – Albert Einstein

What We Know about the Coolidge Tube

Townsend Brown’s first experiments with the Coolidge tube remind us that breakthroughs often come from unexpected places. What began as a teenager’s bold idea evolved into a lifetime of research that challenged scientific norms. Though dismissed by some, his findings continue to inspire those exploring advanced propulsion and energy systems. As our understanding of high-voltage physics grows, the groundwork Brown laid becomes even more relevant.

Which part of Brown’s original setup would you revisit first to validate or challenge his early observations?

Your Work Matters

When I look back at Brown’s earliest setups, salvaged parts, handwritten notes, and a deep sense that something was waiting to be uncovered, I’m reminded how much of this work still begins the same way.

Sometimes we’re not building from blueprints. We’re building from instincts, anomalies, and questions that keep showing up.

If your work lives in that space, between what’s known and what might be, I’d be interested in hearing about it. No agenda. Just a shared appreciation for the kind of thinking that doesn’t always fit inside conventional boundaries.

📩 Feel free to send a note to 👉 letstalk@larrydeavenport.com or schedule a time to talk via phone or Zoom.

Time has a way of circling back to the people and ideas that mattered. Maybe this is one of those moments.

About the Author

Larry Deavenport is a researcher, speaker, and educator with more than 40 years of experience exploring the frontier of electrokinetics, which he calls energy in motion. As founder of Deavenport Technology, he is dedicated to equipping innovators, researchers, and engineers with the clarity, tools, and mentorship they need to transform scattered theories into working prototypes.

Larry’s work focuses on bridging the gap between curiosity-driven experimentation and practical application. His teaching combines structured principles, hands-on demonstrations, and one-on-one guidance to help learners refine breakthroughs and accelerate discoveries. Through his keynotes, workshops, mentoring programs, and his two signature master courses, Larry inspires a new generation of pioneers to explore advanced gravitics and motion-based energy systems that align with natural forces and reduce environmental impact.

Passionate about both discovery and education, Larry continues to share his research and insights at conferences, in collaborative forums, and through his growing platform at Deavenport Technology. His mission is to guide bold thinkers who are ready to move from possibility into progress, shaping the future of sustainable energy and redefining what is possible.

References

- British Patent No. 300,311 (1928) – Method of and Apparatus for Producing Force or Motion by Thomas Townsend Brown, Available via Espacenet Patent Database

- Electrogravitics Systems: Reports on a New Propulsion Methodology by Thomas Valone, PhD (2004), Integrity Research Institut, https://www.integrityresearchinstitute.org

- The Parallel Universe of T. Townsend Brown by Paul Schatzkin (ongoing biography project), Extensive archival research and unpublished material, https://www.ttbrown.com

- Secrets of Antigravity Propulsion by Paul A. LaViolette, PhD (2008), Bear & Company – In-depth review of Brown’s early experiments and potential implications

- Jean-Louis Naudin’s Experimental Replications, Documented setups inspired by Brown’s work, including Coolidge tube configuration, http://jnaudin.free.fr

- Denison University Archives – Dr. Paul Biefeld Papers, Primary documents, correspondence, and research from Brown’s time at Denison, https://denison.edu

- Falcon Space & APEC Conference Archives, Includes discussions and modern test results of early Brown-style high-voltage setup, https://www.altpropulsion.com

Passionate about both discovery and education, Larry continues to share his research and insights at conferences, in collaborative forums, and through his growing platform at Deavenport Technology. His mission is to guide bold thinkers who are ready to move from possibility into progress, shaping the future of sustainable energy and redefining what is possible.