Townsend Brown and Robert Millikan – At a Glance

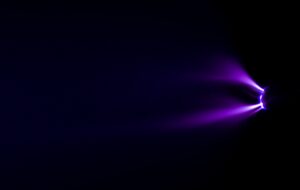

The early relationship between Townsend Brown and Robert Millikan reveals the tension between scientific tradition and emerging ideas. Brown arrived at Caltech eager to share his research on electrogravitics, hoping to find support for his bold theories. Instead, he was met with resistance. Dr. Robert Millikan, a Nobel Prize-winning physicist and key figure at Caltech, dismissed Brown’s work and advised him to focus on formal studies. This rejection was more than personal. It symbolized the challenge of introducing disruptive ideas into established institutions. The experience sent Brown on a different path, one rooted in curiosity, risk, and independent research.

Read time: 5 minutes, 30 seconds

Introduction

Townsend Brown and Robert Millikan stand at the center of one of the most telling moments in early 20th-century scientific conflict.

When big ideas collide with tradition, the result can be revealing. Townsend Brown, a passionate young innovator, brought his discoveries in electrogravitics to Caltech with high hopes.

Caltech didn’t offer support. Instead, its faculty dismissed Brown’s ideas, questioned his credibility, and reinforced the weight of institutional convention. This is the story of the Caltech Rejection, and why it mattered.

Early Ambition Meets Cold Reception

The Caltech Rejection involving Townsend Brown and Robert Millikan began with high hopes and youthful optimism.

Fresh from his success at a local science contest in Zanesville, Ohio, Brown arrived at Caltech energized by his early recognition and hopeful about gaining support for his research. He believed his work on capacitor behavior and gravitation could spark genuine academic interest. But the faculty, steeped in classical views of physics, showed no interest.

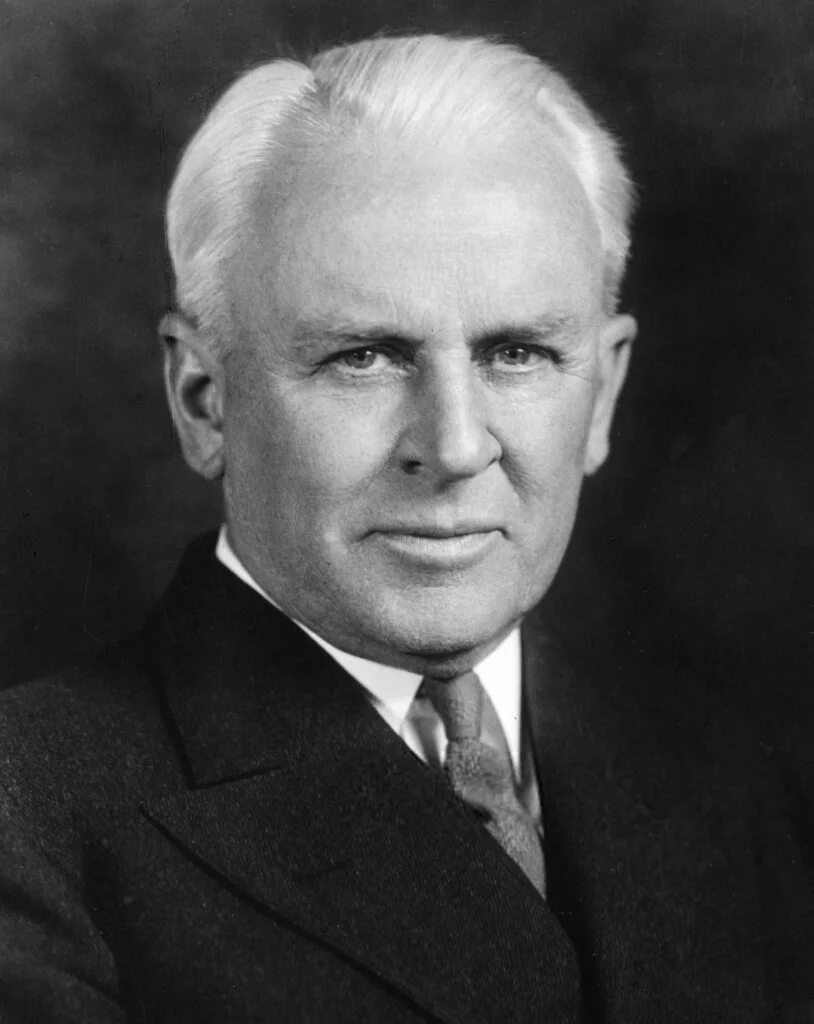

Among them was Dr. Robert Millikan, a towering figure in science who had received the Nobel Prize for measuring the elementary charge of the electron and verifying Einstein’s photoelectric equation. Millikan, however, saw no promise in Brown’s theory. In a private conversation with Brown’s father, Lewis, Millikan allegedly remarked that Townsend was “wasting his time” and urged him to focus on formal studies.

Scientific Credentials and Institutional Bias

Understanding the clash between Townsend Brown and Robert Millikan requires context about both men’s backgrounds.

Millikan’s perspective came from decades of traditional research. His famous oil-drop experiment in 1910 precisely measured the electron’s charge, solidifying the foundations of classical physics. In 1916, he confirmed Einstein’s controversial photoelectric equation, lending credibility to quantum theory and determining Planck’s constant.

In 1921, Millikan became director of the Norman Bridge Laboratory of Physics at Caltech and helped transform the school into a leading research institution. Yet despite his groundbreaking work, he continued to favor Newtonian and ether-based physics during Brown’s time at Caltech.

Brown extended multiple invitations to faculty to witness his experiments, but none accepted. Caltech faculty shut every door Brown tried to open in pursuit of recognition. This rejection not only lowered his morale, it also revealed the uphill battle that any disruptive idea would face in academic environments governed by hierarchy and precedent.

The Pivot to Denison College

After the Caltech Rejection, Townsend Brown and Robert Millikan’s paths diverged: one rooted in tradition, the other in risk-taking.

Disheartened, Brown left Caltech after one year. He later enrolled at Denison College in Granville, Ohio. There, he met Dr. Paul Biefeld, who had once studied with Albert Einstein at the University of Munich. Unlike Millikan, Biefeld was open-minded and encouraged Brown to explore his theories further.

Together, they began conducting experiments that would eventually lead to what Brown termed the “Biefeld-Brown Effect,” the basis for his first patent, British Patent 300,311. With Biefeld’s support, Brown gained the scientific validation Caltech had denied him.

“The greatest leader is not necessarily the one who does the greatest things. He is the one who gets people to do the greatest things.”

—Ronald Reagan

Townsend Brown and Robert Millikan – What We Know

Townsend Brown’s experience at Caltech highlights the tension between innovation and institutional acceptance. Millikan contributed greatly to science, but his dismissal of Brown’s ideas reveals how even brilliant minds can resist what challenges the status quo. Brown’s rejection wasn’t just academic—it was a missed opportunity to nurture a pioneer. Yet Brown persisted, and his work continues to inspire those exploring electrogravitics and beyond.

How do you determine whether to pursue a theory when respected voices in your field reject it outright?

Want to Stay in the Loop?

Brown may have been turned away from Caltech, but he didn’t stop. He sought out people who would listen, asked better questions, and followed the science wherever it led. That spirit of persistence—outside the gatekeepers—is what continues to move this field forward.

If you’re the kind of person who stays curious, pursues what the evidence reveals, and appreciates thoughtful connection with others on a similar path, I’d be glad to welcome you into my network.

You’ll receive my weekly email, where I share updates on emerging experiments, overlooked insights, replication studies, and ongoing conversations happening in electrogravitics and related fields.

To get started, visit the signup section on my home page and download your complimentary eBook:

“To Understanding Electro-Kinetics in 10 Minutes.”

It’s a brief starting point to a much deeper body of work—and a meaningful way for us to stay connected as the conversation continues.

📩 If you’d like to introduce yourself or talk through what you’re working on, feel free to schedule a time to connect.

The more voices we bring together, the more this work begins to take shape.

About the Author

Larry Deavenport is a researcher, speaker, and educator with more than 40 years of experience exploring the frontier of electrokinetics, which he calls energy in motion. As founder of Deavenport Technology, he is dedicated to equipping innovators, researchers, and engineers with the clarity, tools, and mentorship they need to transform scattered theories into working prototypes.

Larry’s work focuses on bridging the gap between curiosity-driven experimentation and practical application. His teaching combines structured principles, hands-on demonstrations, and one-on-one guidance to help learners refine breakthroughs and accelerate discoveries. Through his keynotes, workshops, mentoring programs, and his two signature master courses, Larry inspires a new generation of pioneers to explore advanced gravitics and motion-based energy systems that align with natural forces and reduce environmental impact.

Passionate about both discovery and education, Larry continues to share his research and insights at conferences, in collaborative forums, and through his growing platform at Deavenport Technology. His mission is to guide bold thinkers who are ready to move from possibility into progress, shaping the future of sustainable energy and redefining what is possible.

References

- Millikan, R.A., The Electron and the Light-Quant from the Experimental Point of View (1924), This post is currently being edited.

- Encyclopedia Britannica, “Robert Andrews Millikan”

- Brown, T.T., British Patent 300,311 (1928)

- Schatzkin, Paul. The Boy Who Invented Television