At a Glance: Brown Legacy in Electrokinetics

The Brown legacy in electrokinetics is not measured by financial wealth or celebrity but by lasting scientific contribution. Townsend Brown’s patents stretched across aviation, environmental systems, and energy generation, and modern researchers continue to test and validate his designs. From influencing experimental propulsion to sparking new interest in advanced energy concepts, his work remains a source of inspiration. His true success is found in the enduring impact of discoveries that continue to shape science and innovation.

Read time: 6 minutes, 30 seconds

Introduction: Redefining Success in the Brown Legacy in Electrokinetics

When people ask if Townsend Brown was successful, the answer depends on how success is defined. In today’s culture, achievement is often judged by wealth, celebrity status, or popularity. By those measures, Brown might appear overlooked. But success can also be measured by discovery, persistence, and the ability to shape future generations of innovators. Through decades of experiments, patents, and influence, the Brown legacy in electrokinetics continues to resonate. His pursuit was not for riches but for discoveries that could change the course of science.

A Legacy Beyond Wealth

Townsend Brown was born into privilege in the early twentieth century, but financial gain was never his pursuit. Unlike many inventors who sought fame or fortune, Brown directed his inheritance toward nonprofits and devoted his life to research. His deepest ambition was not to leave behind riches but to be remembered for discoveries that could benefit humanity.

Alongside Dr. Paul Biefeld, Brown identified the phenomenon later called the Biefeld-Brown Effect, laying the foundation for his lifelong study of electrogravitics and electrokinetics. He chose to prioritize scientific contribution over personal fortune, filing patents and publishing research in hopes of building credibility for ideas that challenged convention.

This decision often meant he stood outside mainstream recognition, but it also positioned him as a pioneer. By investing in ideas that would outlive him, Brown shaped a legacy defined not by material wealth but by scientific vision that continues to influence researchers today.

Patents that Shaped Electrokinetics

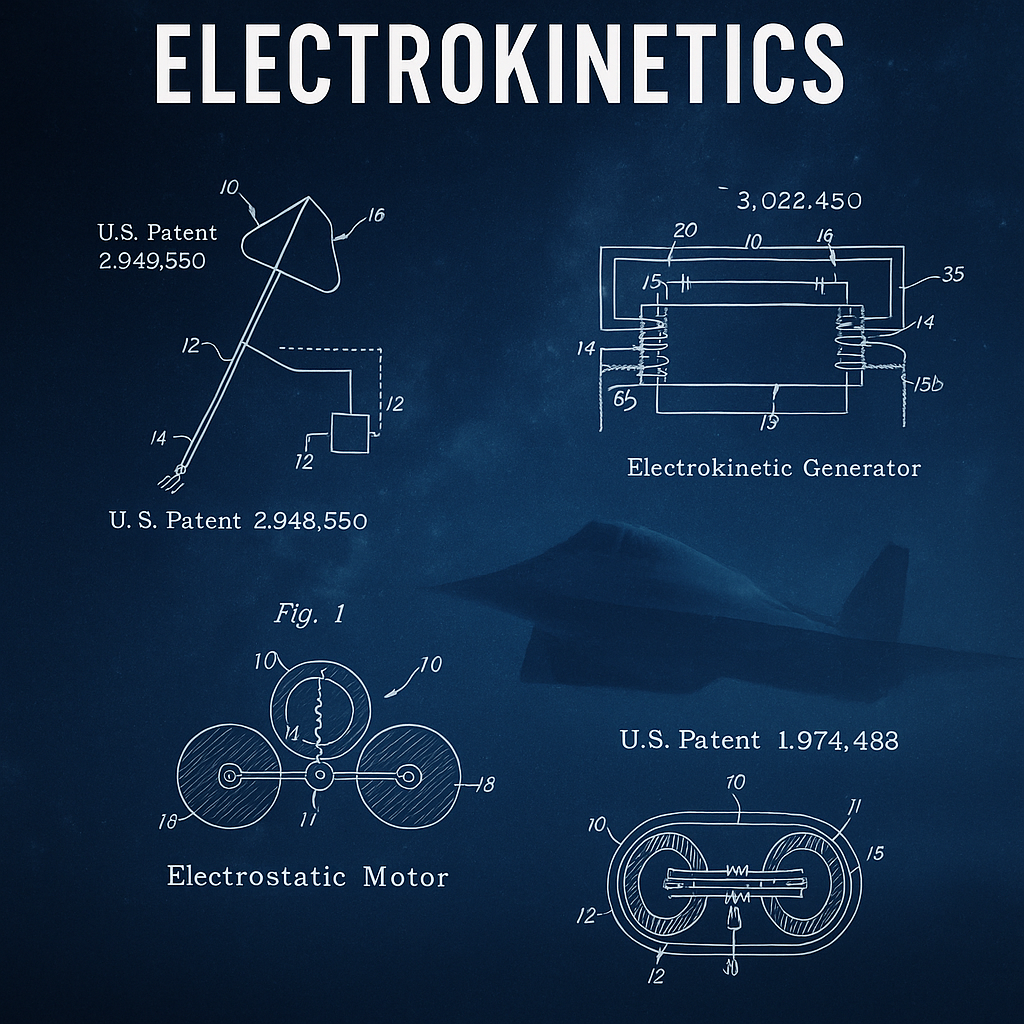

A central part of the Brown legacy in electrokinetics is the series of patents he secured across his lifetime. These were not just technical filings but milestones in a body of work that sought to prove electrokinetic principles could be applied in real-world systems.

His British Patent 300,311, Methods of Producing Force or Motion, provided one of the earliest outlines of his propulsion research. In the United States, he went on to secure patents including Electrostatic Motor (1,974,483), Electrokinetic Apparatus (2,949,550), Electrokinetic Transducer (3,018,394), Electrokinetic Generator (3,022,430), and Electrokinetic Apparatus (3,187,206). Together, these patents pointed toward new possibilities in propulsion and motion-based energy.

Brown’s innovations were not confined to aviation. Patent 2,417,347 described a vibration damper for road-grading equipment. Patent 2,207,576 outlined a process for removing suspended matter from gases, applied in refinery operations to improve air purification. Patent 3,196,296 described a steam and gas-powered generator used aboard large ships to produce alternating current in isolated environments. His final patent, 3,296,491, focused on producing ions and electrically charged aerosols, applied in early cloud-seeding programs for weather modification.

These patents reveal the breadth of Brown’s vision. He was not content to chase only one application. Instead, he explored how electrokinetic principles could transform transportation, energy, industry, and even atmospheric science.

Replications and Renewed Interest

The true test of an inventor’s impact is whether others can build upon their work. The Brown legacy in electrokinetics has endured through decades of replications and refinements.

In the 1990s, Larry Deavenport and Russel Anderson constructed and demonstrated Brown’s electrokinetic apparatus, proving that his designs could move beyond paper. Around the same time, Dr. J.L. Naudin in France experimented with several of Brown’s patents, achieving a breakthrough in 2006 when he built a flying drone based on U.S. Patent 2,949,550.

More recently, Brown’s ideas have resurfaced in the hands of innovators. In 2020, Dr. Charles Buhler and Andrew Aurigema of Exodus Propulsion Technologies filed a patent for asymmetric capacitors (WO2020159603A2), explicitly referencing Brown’s discoveries. In 2023, Mark Sokol of Falcon Space LLC performed a successful vacuum chamber test of a Brown-inspired electrokinetic apparatus, further validating that his principles remain viable in modern experimental propulsion.

Each of these replications demonstrates that Brown’s research was not theoretical speculation. Instead, it continues to stand as a foundation that others are building upon, decades after his original work.

Measuring Success Through Influence

If success is measured by commercial adoption, Townsend Brown might be considered overlooked. His inventions did not achieve mass production, and his name is rarely found in mainstream scientific histories. Yet measuring success only by wealth or recognition misses the deeper impact of his work.

Brown influenced hundreds of inventors and researchers, including Glenn Hagen, Alexander Seversky, Ernest Okress, Ron Kita, Charles Buhler, and Andrew Aurigema. His studies attracted military interest, leading to funded projects behind the scenes. The possibility that his research contributed to classified aerospace programs, such as the development of stealth technology, suggests that his influence reached further than public records reveal.

Brown understood that his discoveries might not gain full recognition in his lifetime. Yet he pursued them with the conviction that they would shape the future. His legacy is measured not in personal gain but in the ripple effect of his ideas across generations of scientists, engineers, and experimenters.

“The greatest use of a life is to spend it on something that will outlast it.” – William James

What We Know About the Brown Legacy in Electrokinetics

The Brown legacy in electrokinetics demonstrates that true success is not always tied to wealth or celebrity. Through decades of persistence, patents, and influence, Townsend Brown contributed ideas that continue to inspire. His work spans multiple industries, his devices have been replicated across continents, and his discoveries remain part of modern propulsion research.

What we know is simple: Brown’s vision outlived him. It continues to shape conversations about advanced energy, experimental propulsion, and technologies that align with natural forces. The measure of his success is not fortune but a legacy that endures.

How do you define success? Is it what is achieved in a single lifetime, or the discoveries that continue to inspire generations to come?

Want to Stay in the Loop?

Curiosity never stops with a single experiment. The Brown legacy in electrokinetics reminds us that progress happens when ideas are shared and tested by many voices. If you want to follow along with the latest replications, insights, and conversations in this field, here’s how we can stay connected:

You’ll receive my weekly email, where I share updates on emerging experiments, overlooked insights, replication studies, and ongoing conversations happening in electrogravitics and related fields.

To get started, visit the signup section on my home page and download your complimentary eBook:

“To Understanding Electro-Kinetics in 10 Minutes.”

It’s a brief starting point to a much deeper body of work, and a meaningful way for us to stay connected as the conversation continues.

📩 If you’d like to introduce yourself or talk through what you’re working on, feel free to schedule a time to connect.

The more voices we bring together, the more this work begins to take shape.

About the Author

Larry Deavenport is a researcher, speaker, and educator with more than 40 years of experience exploring the frontier of electrokinetics, which he calls energy in motion. As founder of Deavenport Technology, he is dedicated to equipping innovators, researchers, and engineers with the clarity, tools, and mentorship they need to transform scattered theories into working prototypes.

Larry’s work focuses on bridging the gap between curiosity-driven experimentation and practical application. His teaching combines structured principles, hands-on demonstrations, and one-on-one guidance to help learners refine breakthroughs and accelerate discoveries. Through his keynotes, workshops, mentoring programs, and his two signature master courses, Larry inspires a new generation of pioneers to explore advanced gravitics and motion-based energy systems that align with natural forces and reduce environmental impact.

Passionate about both discovery and education, Larry continues to share his research and insights at conferences, in collaborative forums, and through his growing platform at Deavenport Technology. His mission is to guide bold thinkers who are ready to move from possibility into progress, shaping the future of sustainable energy and redefining what is possible.

References

- Brown, T.T. (1928). Methods of Producing Force or Motion. British Patent 300,311.

- Brown, T.T. (1934). Electrostatic Motor. U.S. Patent 1,974,483.

- Brown, T.T. (1960). Electrokinetic Apparatus. U.S. Patent 2,949,550.

- Brown, T.T. (1962). Electrokinetic Transducer. U.S. Patent 3,018,394.

- Brown, T.T. (1962). Electrokinetic Generator. U.S. Patent 3,022,430.

- Brown, T.T. (1965). Electrokinetic Apparatus. U.S. Patent 3,187,206.

- Brown, T.T. (1947). Vibration Damper for Road Grading Equipment. U.S. Patent 2,417,347.

- Brown, T.T. (1940). Method and Apparatus for Removing Suspended Matter from Gases. U.S. Patent 2,207,576.

- Brown, T.T. (1965). Electric Generator. U.S. Patent 3,196,296.

- Brown, T.T. (1967). Method and Apparatus for Producing Ions and Electrically Charged Aerosols. U.S. Patent 3,296,491.

- Buhler, C., & Aurigema, A. (2020). Electrostatic Propulsion Device Utilizing Asymmetric Capacitors. WO2020159603A2.

- Naudin, J.L. (2006). Lifter v6.3 UAV Project. JLN Labs. Retrieved from http://jnaudin.free.fr

- Sokol, M. (2023). Falcon Space LLC Vacuum Chamber Tests. Falcon Space.

- Anderson, R., & Deavenport, L. (1990s). Electrokinetic Apparatus Demonstrations. Conference presentations and private research.