Biefeld-Brown Effect Tests in France: At a Glance

The Biefeld-Brown Effect took a leap forward when Townsend Brown traveled to France to conduct long-awaited vacuum tests. Working with Société National de Construction Aeronautiques du Sud Ouest (SNCASO), Brown was finally able to put to rest the persistent myth that his experiments were nothing more than ion wind illusions. In a vacuum chamber reduced to one billionth of atmospheric pressure, his asymmetric capacitors demonstrated undeniable thrust. This milestone helped cement electrogravitics as a legitimate field of inquiry and laid the foundation for further alternative propulsion studies.

Read time: 5 minutes

Introduction

Townsend Brown spent decades chasing scientific validation for a theory few wanted to believe: that electricity and gravity were connected through a force he called electrogravitics. Though early tests ruled out ion wind, skeptics persisted. It wasn’t until Brown traveled to France and partnered with SNCASO that he had the chance to conduct definitive tests. Inside a high-grade vacuum chamber, his technology delivered, and the world of propulsion would never be quite the same.

Breakthrough in a Bottle: Brown’s Early Sealed Tests

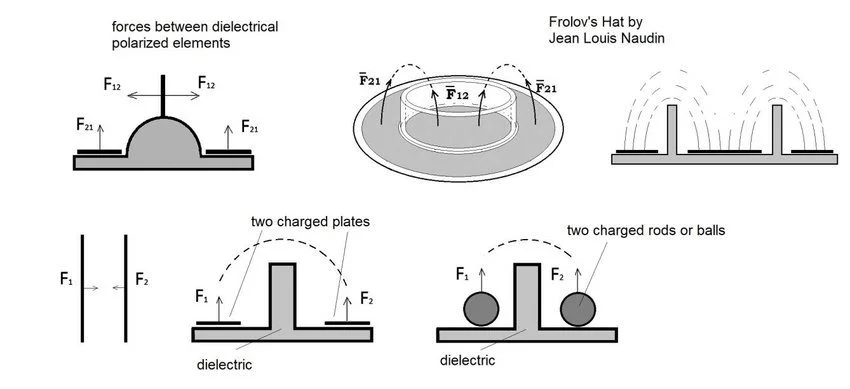

Townsend Brown spent years refining experiments to rule out ion wind as the cause of propulsion in his gravitator devices. As early as his first British patent (No. 300,311), Brown emphasized the airtight construction of his components; stacking lead plates with dielectric membranes and sealing them thoroughly to isolate any external airflow. He even submerged devices in high dielectric mineral oil to eliminate atmospheric interference.

These experiments pointed clearly to a non-aerodynamic force at play. Still, the scientific community demanded one thing: results in a vacuum.

Crossing the Channel: Brown Heads to France

In 1956, Brown was invited to test his gravitator systems at SNCASO. It was a perfect opportunity. SNCASO’s large vacuum chamber allowed Brown to conduct vertical lift tests in controlled, airless conditions. The skeptics could no longer hide behind claims of ion wind or misinterpretation.

Brown’s experiments involved compact, five-inch asymmetric capacitors, smaller cousins of his earlier Hawaii-tested models. Subjected to a near-perfect vacuum (1.01325 × 10⁻⁷ atm), these devices moved. Not only did they move, they moved faster than in atmospheric conditions.

The Tipping Point: A Shift in Scientific Reception

Despite the elegance of Brown’s previous oil-submersion tests and his vacuum tube demonstrations, the French trials were the ones that stuck. They offered the visual, repeatable, controlled results physicists had demanded for decades. A device achieving thrust in a vacuum defied traditional propulsion theory and vindicated Brown’s lifelong pursuit.

Though not immediately embraced by mainstream science, the SNCASO tests marked a critical turning point.

Echoes in the Chamber: Modern Reenactments of the Effect

Brown may have laid the groundwork, but the investigation into the Biefeld-Brown Effect didn’t end there. Researchers like Mark Sokol and Andrew Aurigema have since carried the torch, recording modern replications of electrokinetic movement in vacuum environments. You can explore their findings through organizations like Alt Propulsion Labs (APEC) and their available videos.

Each new generation picks up where Brown left off, proving that science, when powered by persistence, keeps moving forward.

“Much of the credit for this research is due to Dr. Paul Biefeld, Director of Swazey Observatory. The writer is deeply indebted to him for his assistance and for his many valuable and timely suggestions.” – Thomas Townsend Brown

Biefeld-Brown Effect Tests in France – What We Know

The Biefeld-Brown Effect has often been misunderstood, dismissed as a product of ion wind or experimental error. But Townsend Brown’s vacuum chamber tests in France told a different story. His devices moved in near-total vacuum, something classical physics couldn’t easily explain. These results offered strong evidence for a real electrokinetic force and laid a foundation for future research in field-based propulsion systems. Brown’s legacy reminds us that persistent testing and open-minded exploration can reshape what’s considered possible.

What might today’s engineers uncover if they reexamine Brown’s work through the lens of modern electrokinetic design and advanced materials?

Let’s Rethink the Frontier Together

If you’re experimenting with high-voltage setups, revisiting shelved theories, or navigating the edge of electrokinetic science, you don’t have to go it alone.

I work with researchers and science enthusiasts who are serious about pushing boundaries with clarity and rigor. Sometimes that means returning to fundamentals. Other times, it means exploring better questions together.

📩 If you’re looking for a mentor, email me at 👉 letstalk@larrydeavenport.com. I’d be glad to connect.

Reach out on LinkedIn or schedule a time to talk.

Not all breakthroughs happen in the lab. Some begin with the right conversation.

About the Author

Larry Deavenport is a researcher, speaker, and educator with more than 40 years of experience exploring the frontier of electrokinetics, which he calls energy in motion. As founder of Deavenport Technology, he is dedicated to equipping innovators, researchers, and engineers with the clarity, tools, and mentorship they need to transform scattered theories into working prototypes.

Larry’s work focuses on bridging the gap between curiosity-driven experimentation and practical application. His teaching combines structured principles, hands-on demonstrations, and one-on-one guidance to help learners refine breakthroughs and accelerate discoveries. Through his keynotes, workshops, mentoring programs, and his two signature master courses, Larry inspires a new generation of pioneers to explore advanced gravitics and motion-based energy systems that align with natural forces and reduce environmental impact.

Passionate about both discovery and education, Larry continues to share his research and insights at conferences, in collaborative forums, and through his growing platform at Deavenport Technology. His mission is to guide bold thinkers who are ready to move from possibility into progress, shaping the future of sustainable energy and redefining what is possible.

References

- Brown, T. T. (1928). British Patent No. 300,311. A Method of and an Apparatus or Machine for Producing Force or Motion.

- [Available through UK Intellectual Property Office archives]

- Valone, Thomas. (2000). Electrogravitics Systems: Reports on a New Propulsion Methodology. Integrity Research Institute.

- https://www.integrityresearchinstitute.org

- APEC (Alternative Propulsion Engineering Conference). Experimental validation videos and discussions of the Biefeld-Brown Effect in vacuum by Mark Sokol and Andrew Aurigema.

- https://www.altpropulsion.com

- NASA Technical Memorandum 107166. (1992). “An Overview of Experimental Concepts for Electric Propulsion”

- https://ntrs.nasa.gov

- Hathaway, George D. (1991). Electrogravitic and Electrokinetic Propulsion. Electric Spacecraft Journal, Issue #8–10.

- https://electricspacecraft.org (archival access or print issues)

- LaViolette, Paul A. (2008). Secrets of Antigravity Propulsion: Tesla, UFOs, and Classified Aerospace Technology. Bear & Company.

- (Caution: speculative content, but widely referenced in the electrogravitics community)