Electrogravitics – At a Glance

Electrogravitics, once dismissed as fringe science, is reemerging in conversations about future propulsion. This blog traces its origins to the 1920s, when a young Townsend Brown observed unexplained motion from asymmetric capacitors using a Coolidge X-ray machine. With encouragement from Dr. Paul Biefeld, Brown documented what became known as the Biefeld-Brown Effect—suggesting a link between electricity and gravity. Despite skepticism, this early research may hold the key to silent, fuel-free propulsion. As interest grows among engineers and innovators, electrogravitics is no longer just a curiosity. It’s a field ready for rediscovery and modern exploration.

Read time: 5 minutes, 30 seconds

Introduction

From military disclosures to YouTube debates, the term electrogravitics is circulating more than ever. Scientists, journalists, and engineers are asking: Could this once-dismissed field offer clues to propulsion systems beyond rockets and jet fuel?

To answer that, we have to return to the 1920s, to a young experimenter in Ohio, a salvaged X-ray machine, and a discovery that made capacitors move. Townsend Brown didn’t just observe a phenomenon; he may have uncovered the beginning of a whole new field: energy in motion. What if the key to silent, fuel-free propulsion was discovered in the 1920s and ignored for nearly a century?

Where It All Began: Electrogravitics

The word electrogravitics was first introduced in British Patent No. 300,311, filed by Thomas Townsend Brown. Working with Dr. Paul Biefeld at Denison University, Brown experimented with asymmetric capacitors under high-voltage conditions and observed physical motion in the devices. This phenomenon, now known as the Biefeld-Brown Effect, defied conventional electrical theory and suggested a relationship between electric fields and gravity.

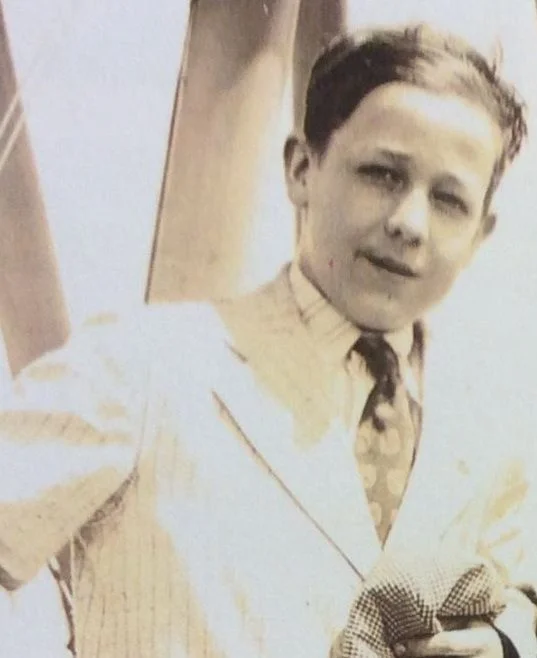

Photo: T Townsend Brown at age 14, Courtesy of Thomas Townsend Brown Facebook Page

Key Terms:

Biefeld-Brown Effect: The observed propulsion-like motion resulting from high voltage applied to asymmetric capacitors.

Asymmetric Capacitor: A capacitor with electrodes of unequal size, used to create a directional electric field.

Electrogravitics: A theoretical field exploring the interaction between electricity and gravity.

The Experiments That Moved

A Curious Young Mind

Townsend Brown was born in 1905 in Zanesville, Ohio. With a love for science fiction and access to tools beyond his years, he began experimenting with an old Coolidge X-ray machine. While exploring its function, he noticed something strange. There was movement. After tracing the cause, he found it wasn’t from mechanical vibration or magnetic influence but from the capacitor itself.

First Public Demonstration

In 1922, Brown demonstrated this phenomenon at a local science contest, winning recognition that would later fade as his ideas ran up against conventional academia. He later enrolled at Caltech, where physicist Robert Millikan told him his ideas about gravity were “impossible.” Disheartened, Brown left and continued his work independently.

The Biefeld Connection

At Denison University, Brown partnered with Dr. Paul Biefeld, who encouraged deeper research. It was here that Brown refined his work on asymmetric capacitors, setting the stage for what we now call electrogravitics.

The Bigger Possibility

Brown’s early experiments sparked decades of curiosity but also skepticism. Today, the Biefeld-Brown Effect remains a debated phenomenon. Is it simply ion wind? Or is it an early glimpse into electrogravitics, propulsion systems that don’t rely on combustion?

If there is indeed a deeper interaction between high-voltage electrostatic fields and gravity, or inertia, then we’re looking at more than just academic interest. We’re looking at the foundation for silent, fuel-free propulsion.

If you’re an engineer, researcher, or curious innovator, Brown’s journey isn’t just a story; it’s a possible blueprint. What could we build if we picked up where he left off?

“The reasonable man adapts himself to the world; the unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore, all progress depends on the unreasonable man.”

— George Bernard Shaw

Electrogravitics – What We Know

Townsend Brown’s discoveries were not just early curiosities—they were foundational glimpses into a field that challenges our understanding of motion, energy, and gravity. Electrogravitics, born from a teenager’s experiment with an X-ray machine, remains one of the most intriguing possibilities in propulsion science. Today, with advancements in materials, computing, and experimental design, we’re better equipped than ever to revisit his work.

What aspect of electrogravitics fascinates you most, and where does your curiosity suggest this road might lead?

Let’s Talk Discovery

If you’re navigating similar territory, tinkering with high-voltage setups, chasing the edge of known science, or revisiting theories others set aside long ago, you don’t have to do it in isolation.

I work with researchers and science enthusiasts who are serious about refining their work and thinking through the challenges that come with charting new ground. Sometimes that means revisiting fundamentals. Sometimes it means asking better questions together.

📩 If you’re looking for a mentor or simply someone who understands the long arc of curiosity, I’d be honored to connect.

You can connect with me on LinkedIn or schedule a conversation.

Breakthroughs don’t always happen in the lab. Sometimes, they begin with a shared conversation.

About the Author

Larry Deavenport is a researcher, speaker, and educator specializing in electro-kinetics, energy in motion. Through his company, Deavenport Technology, he equips science enthusiasts, researchers, and engineers with the core principles needed to refine breakthroughs and accelerate discoveries. Larry shares his expertise through keynotes, workshops, mentoring, and research, inspiring innovation in the ever-evolving field of advanced gravitics research.

References

- Brown, T. T. (1928). British Patent No. 300,311 – Method of and Apparatus for Producing Force or Motion. [Available via Espacenet or Google Patents]

- Valone, Thomas (2004). Electrogravitics Systems: Reports on a New Propulsion Methodology. Integrity Research Institute. https://www.integrityresearchinstitute.org

- NASA Technical Reports Server (NTRS) – Electrogravitics and Field Propulsion: A Literature Review https://ntrs.nasa.gov

- Paul A. LaViolette (2008). Secrets of Antigravity Propulsion: Tesla, UFOs, and Classified Aerospace Technology. Bear & Company.

- Townsend Brown Family Archives (Photos, personal history, unpublished manuscripts) ttps://thomastownsendbrown.com

- Marc Millis, NASA Glenn Research Center – Breakthrough Propulsion Physics Program Summary Report https://www.nasa.gov

- Dr. Paul Biefeld Papers, Denison University Special Collections (for original correspondence and early lab work) https://denison.edu