At a Glance: The Ion Wind Debate

The ion wind debate has been at the center of electrokinetics research for more than a century. Critics argue that Townsend Brown’s devices moved only because of charged air, while Brown and others demonstrated that movement continued in vacuum conditions where air could not play a role. From early experiments in 1709 to modern patents and laboratory replications, the debate is still shaping how scientists view electrogravitics and propulsion.

Read time: 6 minutes

Introduction: Why Ion Wind Matters in Electrokinetics

The ion wind debate is more than a technical footnote. For many, it represents the dividing line between curiosity and breakthrough. If Brown’s devices functioned only because of ionized air currents, then his legacy reduces to clever demonstrations of electrostatics. But if the Biefeld-Brown Effect cannot be explained by ion wind alone, then his research hints at forces we have yet to fully understand. The stakes are not just about airflow but about whether Brown discovered a phenomenon with the potential to reshape propulsion science.

The Case for Ion Wind

Ion wind itself is not new. It was first described in 1709 by Francis Hausbee, an English physicist who observed that high voltage passing through air created a flow of ions. Ever since, high-voltage electrical systems have produced ion wind as a byproduct. By the early 20th century, it was common to assume that unusual movements around high-voltage devices were simply the result of ion wind.

Modern hobbyists have continued the discussion. On YouTube, entire channels feature competitions to build ion thrusters. Jay of The Plasma Channel shows how small lifters can use ionized air currents to create thrust. These demonstrations prove that ion wind can move objects in air. However, the thrust created by Brown’s asymmetric capacitors relied on higher voltages and operated differently from the trickling voltages of ion thruster experiments. This distinction is at the heart of the ion wind debate.

Brown’s Response to the Ion Wind Debate

When Townsend Brown filed his first patent, British Patent 300,311, he made the bold claim that electromagnetism and gravity were connected. Before many physicists even studied his work, critics accused him of mistaking ion wind for a new force.

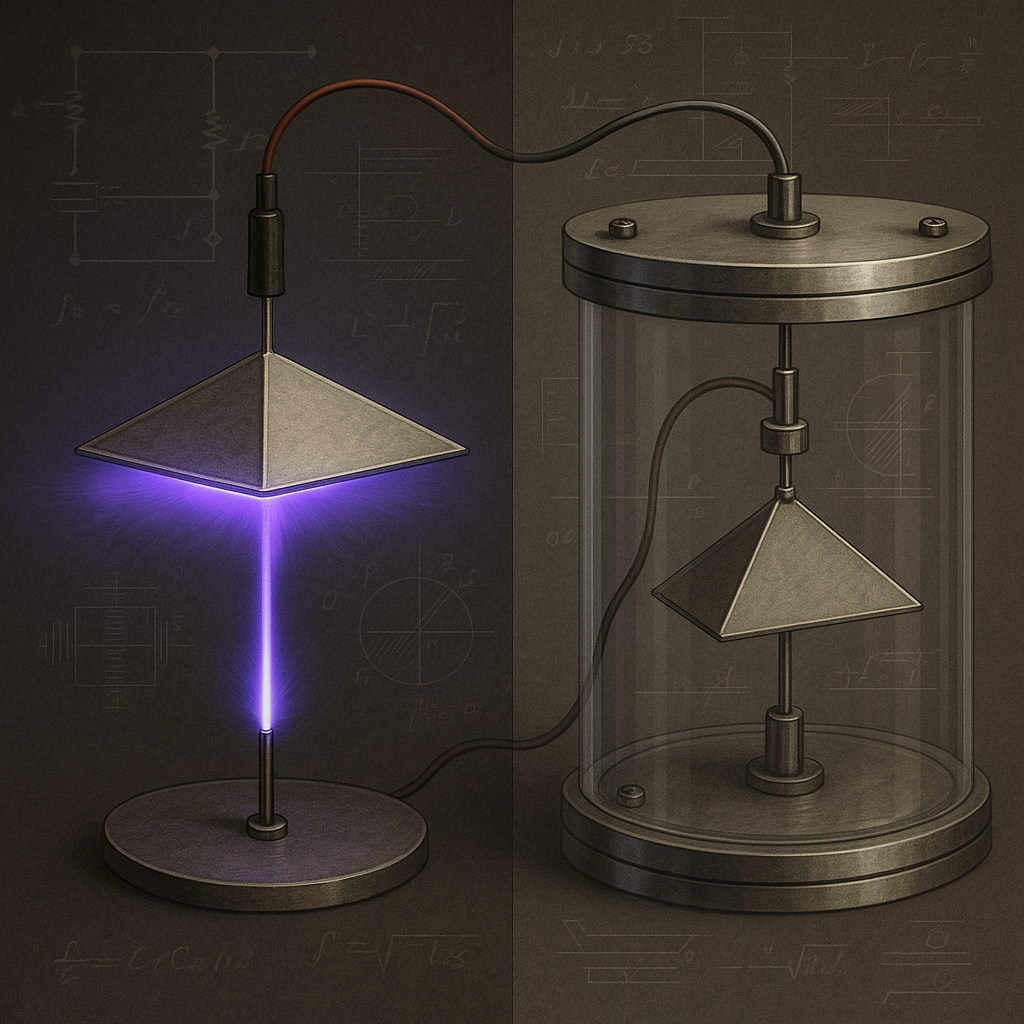

Brown anticipated these objections. He placed his early “gravitators” in high-purity mineral oil, using a strong dielectric to prevent electrical discharge through the air. By insulating his devices, he ensured that any observed movement was not simply the result of air being pushed around electrodes.

Despite these precautions, skepticism followed him throughout his career. The ion wind debate became a constant backdrop to his research, shaping both his experiments and the criticism he faced.

Vacuum Tests That Changed the Story

The strongest counterargument to ion wind came from Brown’s own vacuum tests. In 1956, at SNCASO in France, he tested his devices at a pressure of 3 × 10⁻⁶ torr. Motion was still observed. The following year, similar tests at Agnew Bahnson’s lab in North Carolina confirmed the results.

Later tests in Washington, D.C., during the 1960s and 1970s provided even more insight. As the vacuum chamber was evacuated, movement would disappear at intermediate pressures. But as the chamber approached a deeper vacuum, the effect reappeared — and grew stronger the closer conditions came to a perfect vacuum.

Brown also reported observing what he called a “hyperbolic electrostatic force,” a phenomenon he described as electric dynamics. Family records and correspondence with engineers such as Thurman suggest that Brown believed he had uncovered an entirely new category of force.

The fact that the effect persisted in high vacuum conditions posed a direct challenge to the ion wind explanation.

Modern Replications and a Missed Opportunity

Brown’s tests were not the last word. Over the years, others have repeated his experiments with notable results. In 2007, Dr. J.L. Naudin conducted vacuum tests inspired by Brown’s work and confirmed similar behavior. In late 2024, Mark Sokol of Falcon Space performed a live demonstration of an electrokinetic apparatus based on Brown’s design during an APEC session, drawing attention across the experimental community.

The most striking development came from Exodus Propulsion Technologies. Over the past three years, Dr. Charles Buhler and Andrew Aurigema not only replicated Brown’s work but advanced it. In 2021 they were awarded patent WO202159603A2, titled System and Method for Generating Forces Using Asymmetrical Electrostatic Pressure. The patent describes a propellantless drive system for satellites — an idea that resonates strongly with Brown’s original vision.

These modern findings suggest that dismissing Brown’s research as “just ion wind” may have been a missed opportunity. By labeling his discoveries as misunderstanding, critics may have delayed exploration into forces with real potential for propulsion and energy systems.

“The greatest enemy of knowledge is not ignorance, it is the illusion of knowledge.” — Stephen Hawking

What We Know About the Ion Wind Debate

The ion wind debate illustrates how easy it is to dismiss unusual results with a convenient explanation. Ion wind is real and present in high-voltage systems, but Brown’s vacuum tests and subsequent replications show it cannot be the whole story.

What we know is this: Townsend Brown’s devices challenged conventional assumptions. His careful use of dielectric insulation, his high-vacuum experiments, and modern confirmations point toward phenomena that go beyond simple airflow. The debate is not settled, but the evidence suggests that ion wind is only part of a much larger picture.

How might Brown’s approved patents help us piece together what’s missing from the official research trail?

Explore What Others Are Building

Each experiment, patent, and rediscovery adds another piece to the larger puzzle. By connecting with others who are testing, building, and asking new questions, we keep Brown’s legacy alive, and create the momentum for what comes next.

That’s part of what I aim to do through my Insights & Extras page. It’s where I highlight the work of others, videos, interviews, white papers, and experiments, who are exploring electrogravitics, electro-kinetics, and ion propulsion in meaningful ways. These are the voices and efforts keeping the conversation alive.

If you’ve contributed something to this field, I’d be glad to learn about it and consider featuring it there.

📩 Just send a note to 👉 letstalk@larrydeavenport.com or schedule a time to talk if you’d like to walk me through what you’ve built.

The more we surface, the more we all learn. And the less likely these stories are to disappear again.

About the Author

Larry Deavenport is a researcher, speaker, and educator with more than 40 years of experience exploring the frontier of electrokinetics, which he calls energy in motion. As founder of Deavenport Technology, he is dedicated to equipping innovators, researchers, and engineers with the clarity, tools, and mentorship they need to transform scattered theories into working prototypes.

Larry’s work focuses on bridging the gap between curiosity-driven experimentation and practical application. His teaching combines structured principles, hands-on demonstrations, and one-on-one guidance to help learners refine breakthroughs and accelerate discoveries. Through his keynotes, workshops, mentoring programs, and his two signature master courses, Larry inspires a new generation of pioneers to explore advanced gravitics and motion-based energy systems that align with natural forces and reduce environmental impact.

Passionate about both discovery and education, Larry continues to share his research and insights at conferences, in collaborative forums, and through his growing platform at Deavenport Technology. His mission is to guide bold thinkers who are ready to move from possibility into progress, shaping the future of sustainable energy and redefining what is possible.

References

- Hausbee, F. (1709). Early observations on electrical discharges. Historical accounts in early physics literature.

- Brown, T.T. (1928). Methods of Producing Force or Motion. British Patent 300,311.

- Brown, T.T. (1965). Electrokinetic Apparatus. U.S. Patent 3,187,206.

- Bahnson, A.H. & Brown, T.T. (1956). Vacuum chamber tests at SNCASO, France. Reports cited in historical archives and secondary research.

- Thurman, [Personal correspondence with Townsend Brown]. Family archives, referenced in later summaries of Brown’s work.

- Naudin, J.L. (2007). Vacuum Lifter Replication. JLN Labs. Retrieved from http://jnaudin.free.fr.

- Sokol, M. (2024). Electrokinetic Apparatus Demonstration at APEC Conference. Falcon Space LLC.

- Buhler, C., & Aurigema, A. (2021). System and Method for Generating Forces Using Asymmetrical Electrostatic Pressure. WO202159603A2. World Intellectual Property Organization.

- Hawking, S. (1990s). The greatest enemy of knowledge is not ignorance, it is the illusion of knowledge. Quote attributed.