At a Glance: The Bahnson Brown Antigravity Experiments

Between 1957 and 1958, Bahnson Laboratories in Winston-Salem, North Carolina became the site of one of the boldest explorations into antigravity and field propulsion ever attempted. The work of Thomas Townsend Brown, Agnew H. Bahnson, Jr., and Dr. James Frank King sought to move electrogravitics beyond speculation and into experimental proof. Their vision was nothing less than revolutionary: to show that propulsion without fuel was possible, and to test whether gravity itself could be influenced by electrical and magnetic forces.

Read time: 7 minutes

Introduction: The Bahnson Brown Antigravity Experiments

In the late 1950s, three remarkable individuals converged in a quiet laboratory in North Carolina with a shared vision that challenged conventional aerospace wisdom. Thomas Townsend Brown, already known for his controversial research into electrogravitics, joined forces with wealthy industrialist Agnew H. Bahnson, Jr., and aerospace engineer Dr. James Frank King. Together, they set out to explore whether high-voltage electric fields and advanced electromagnetic interactions could create measurable thrust without combustion or propellant.

Their collaboration represented more than a scientific experiment. It was a daring attempt to prove that the boundaries of physics were not yet fully understood, and that breakthrough propulsion systems might already be within reach.

Visionaries at Work: Brown, Bahnson, and King

Townsend Brown’s long study of the Biefeld-Brown Effect had hinted that high-voltage, asymmetrical capacitors might create directional force. Agnew Bahnson, intrigued by these ideas, offered both financial backing and a laboratory. He brought in his brother-in-law, aerospace engineer Dr. James Frank King, to add technical depth.

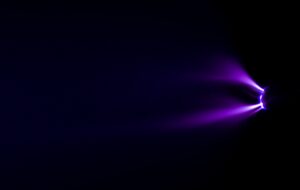

Together, the trio tested small flying discs powered by ballistic electrodes, Tesla coils, and high-voltage DC sources, even experimenting in vacuum chambers to rule out simple ion wind. Surviving photographs, Brown’s notes, and later reviews confirm the work was systematic and ahead of its time. Reports also suggest outside observers, possibly military or government, attended key demonstrations, evidence that the implications were taken seriously.

From Lab Bench to Patents: Engineering Antigravity Concepts

Each researcher transformed lessons from the collaboration into patents that secured their work in the engineering record.

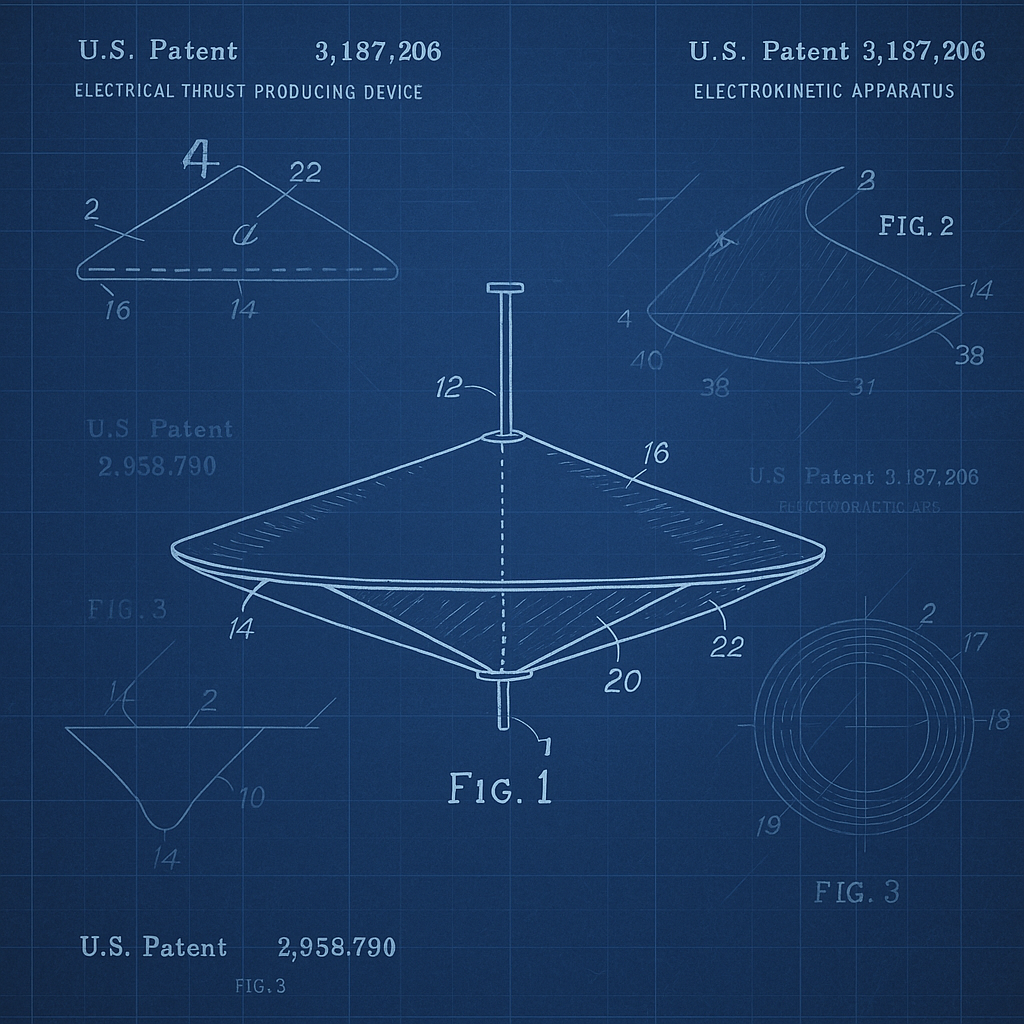

Agnew Bahnson’s 1960 patent described propulsion through asymmetrical electrodes under high voltage, later expanded with steering electrodes for directional control without moving parts. Townsend Brown’s 1965 patent for an “Electrokinetic Apparatus” used shaped electrodes and dielectric materials to amplify thrust, with applications both in air and space. Dr. James Frank King’s 1967 patent took a magnetohydrodynamic approach, using traveling magnetic fields and ionized plasma to generate thrust with built-in stabilization.

Though different in detail, all three patents pointed toward a future of propulsion driven by fields rather than fuel.

Experimental Breakthroughs: What They Discovered

The team confirmed three central insights. First, they showed that circular craft could be steered without moving parts by energizing steering electrodes. Second, they found that combining direct and alternating currents created more precise control of thrust and maneuverability. Finally, they discovered that curved electrodes with graded dielectrics amplified thrust by sharpening field gradients. Together, these findings offered a roadmap for how geometry, materials, and field integration could turn theory into propulsion.

The Legacy of the Bahnson Brown Experiments

Although no deployable antigravity craft emerged, the Bahnson-Brown-King collaboration proved that electrically induced thrust was real, measurable, and controllable. They showed that propulsion could be influenced by design and material choices, laying groundwork for future studies in electrogravitics and plasma propulsion.

Much of what they tested foreshadowed modern work on ion drives and field-based propulsion. In the end, their greatest legacy may be their willingness to pursue radical questions in a modest North Carolina lab, showing that bold ideas can push science forward even outside government facilities and aerospace giants.

“Somewhere, something incredible is waiting to be known.” — Carl Sagan

What We Know About the Bahnson Brown Antigravity Experiments Today

The Bahnson Brown Antigravity Experiments remain one of the most intriguing and well-documented episodes in the search for breakthrough propulsion. Thanks to preserved patents, photographs, and written accounts, we know that this small team achieved results that challenged conventional science and opened the door to new questions.

What is most striking is the courage and curiosity that drove them. In a modest North Carolina laboratory, far removed from the vast facilities of government contractors, three men dared to pursue the possibility that gravity itself could be engineered. Their legacy is not simply in what they discovered, but in the spirit of exploration they embodied. As we look to the future of propulsion, their work stands as a reminder that some of the most important breakthroughs can begin not with massive budgets, but with vision, determination, and the willingness to question what is possible.

What if the experiments of the past were not unfinished stories, but blueprints waiting for the next generation to pick them up?

Your Work Matters

What Brown, Bahnson, and King pursued in their North Carolina lab was more than an experiment. It was a mindset. That same willingness to follow hunches and explore outside convention is what continues to drive discovery today.

If your work lives in that space, between what’s known and what might be, I’d be interested in hearing about it. No agenda. Just a shared appreciation for the kind of thinking that doesn’t always fit inside conventional boundaries.

📩 Feel free to send a note to 👉 letstalk@larrydeavenport.com, or schedule a time to talk if you’d rather speak face to face.

Time has a way of circling back to the people and ideas that mattered. Maybe this is one of those moments.

About the Author

Larry Deavenport is a researcher, speaker, and educator with more than 40 years of experience exploring the frontier of electrokinetics, which he calls energy in motion. As founder of Deavenport Technology, he is dedicated to equipping innovators, researchers, and engineers with the clarity, tools, and mentorship they need to transform scattered theories into working prototypes.

Larry’s work focuses on bridging the gap between curiosity-driven experimentation and practical application. His teaching combines structured principles, hands-on demonstrations, and one-on-one guidance to help learners refine breakthroughs and accelerate discoveries. Through his keynotes, workshops, mentoring programs, and his two signature master courses, Larry inspires a new generation of pioneers to explore advanced gravitics and motion-based energy systems that align with natural forces and reduce environmental impact.

Passionate about both discovery and education, Larry continues to share his research and insights at conferences, in collaborative forums, and through his growing platform at Deavenport Technology. His mission is to guide bold thinkers who are ready to move from possibility into progress, shaping the future of sustainable energy and redefining what is possible.

References

- Brown, T. Townsend. Electrokinetic Apparatus. U.S. Patent 3,187,206, filed August 16, 1960, and issued June 1, 1965.

- Bahnson, Agnew H., Jr. Electrical Thrust Producing Device. U.S. Patent 2,958,790, filed December 22, 1958, and issued November 1, 1960.

- Bahnson, Agnew H., Jr. Electrical Thrust Producing Device with Steering Electrodes. U.S. Patent 3,263,102, filed March 15, 1962, and issued July 26, 1966.

- King, James F. Magnetohydrodynamic Propulsion Apparatus. U.S. Patent 3,322,374, filed June 21, 1963, and issued May 30, 1967.

- Yost, Charles. Electric Spacecraft Journal. Various issues, 1980s–1990s. [Contains reviews of Brown’s notes and Bahnson Laboratory materials.]

- Valone, Thomas. Electrogravitics Systems: Reports on a New Propulsion Methodology. Integrity Research Institute, 2002.

- Valone, Thomas. Electrogravitics II: Validating Reports on a New Propulsion Methodology. Integrity Research Institute, 2004.

- Rauscher, Elizabeth A. Dynamic Fields and Energy Conversion. Tesla Book Company, 1983. [Contextual work on field propulsion and alternative energy.]

- Mullins, Justin. “Antigravity: The Dream That Wouldn’t Die.” New Scientist, July 1999.

- NASA Glenn Research Center. “Ion Propulsion: Past, Present, and Future.” NASA Fact Sheet, 2002.