The Winterhaven Project At a Glance

The Winterhaven Project – At a Glance

Townsend Brown’s postwar work, known as the Winterhaven Project, marked a major evolution in his research. During this pivotal era, Brown rebranded his gravitators as electrokinetic apparatuses to align with accepted scientific terminology and began experimenting with aerodynamic designs, advanced dielectrics, and high-voltage propulsion. His innovative concepts gained the attention of military and aerospace sectors, where interest in saucer-shaped flight and wireless energy was quietly growing. This blog explores the technical changes, the shift in terminology, and the powerful implications of Brown’s midcareer breakthrough in electrokinetics.

Read time: 4 minutes

Introduction

It was the post-World War Two era, and while the world’s attention turned toward jet propulsion and space travel, one man continued chasing something more radical: motion through fields of energy itself. Townsend Brown, once seen as a fringe scientist, was about to step into the spotlight. His journey through what would be known as “The Winterhaven Project” signaled a critical turning point, not just for his research, but for how the world would start to view the possibilities of electrokinetics.

The Winterhaven Project wasn’t just a phase. It was Brown’s bold attempt to bring his theories into a practical, testable reality that could compete with the dominant technologies of the day.

Rebranding the Vision

Between 1952 and 1957, Brown traveled frequently between Pasadena, California, and Cleveland, Ohio, working on what he called the Winterhaven Project. During this time, he moved away from the term “gravitator” and instead referred to his inventions as “electrokinetic apparatuses,” a more scientifically palatable term. This subtle shift allowed Brown to gain credibility and interest from military and aerospace circles. His devices evolved into sleek, disc-shaped capacitors with more aerodynamic profiles, which he believed could reach high speeds when properly energized.

Design Breakthroughs

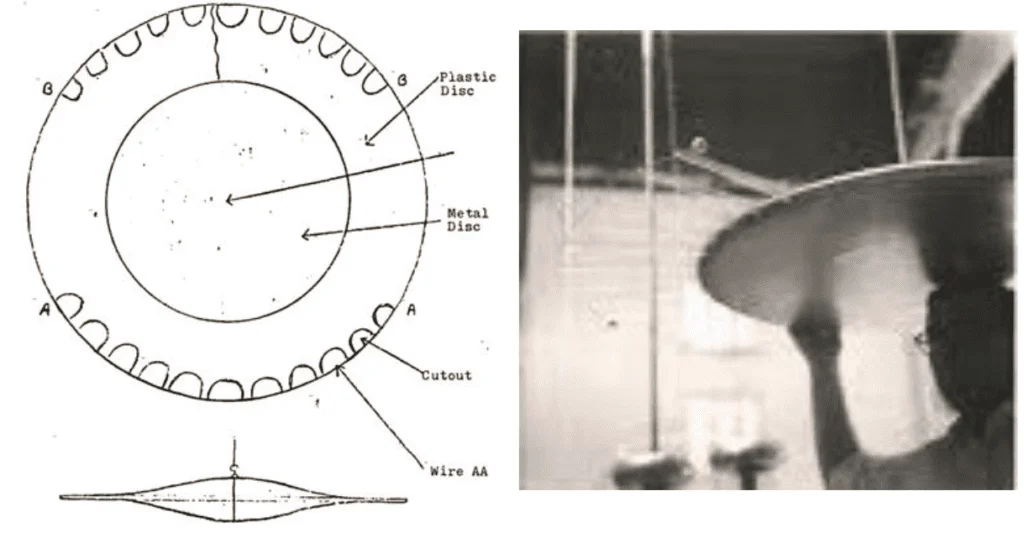

Brown’s U.S. Patent 2,949,550 revealed these innovations. His devices now featured a circular design with dielectric insulators layered over the front to reduce arc overs, short circuits caused by high-voltage discharge. His choice of dielectric materials was critical. After testing various compounds, Brown settled on barium titanate, a ceramic material that held up under the extreme voltages he was exploring. He built models ranging from a few inches wide for vacuum testing to three-foot disks, scaled-down prototypes of what could become full-sized aircraft.

Speed, Power, and the Military Connection

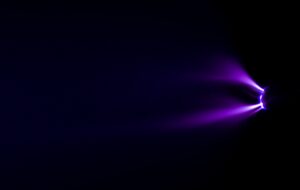

Brown’s experiments were not just conceptual. Reports suggest that using 10 million volts, his disk designs reached speeds exceeding 1,000 miles per hour. Later sources suggested he might be able to achieve speeds approaching 2,500 miles per hour, potentially faster than any jet aircraft of the early 1950s. At a time when the U.S. Air Force was entertaining saucer-shaped aircraft through programs like Canada’s Avrocar, Brown’s designs did not seem farfetched. The Winterhaven Project became his most productive and respected period among peers who typically dismissed electrogravitics as speculative at best.

The Electrokinetic Generator From Propulsion to Wireless Power

Brown didn’t stop at flight. In his later U.S. Patent 3,022,430, he introduced an electrokinetic generator with a dual function. First, it used a flame jet system, or hydromagnetic generator, to produce negatively charged ions in high volumes. This addressed the problem of compact energy systems capable of sustaining propulsion. Second, the ions could be projected across long distances and used to wirelessly charge remote capacitors, an idea reminiscent of Tesla’s experiments with atmospheric electricity. Brown even tested CO₂ as a working gas, showing improved efficiency in ion generation.

Legacy and Forward Motion

The Winterhaven Project concluded in 1957, but Brown’s work did not end. He soon accepted a position at Bahnson Laboratories in North Carolina, where he continued to test electrokinetic propulsion systems. But it was during the Winterhaven Project that his ideas reached their peak exposure and military interest. His designs, concepts, and terminology left a lasting impression, and many believe they laid the foundation for research that continued, often quietly, well into the modern era.

“Progress is born of curiosity and survives only through courage.” – Townsend Brown

The Winterhaven Project – What We Know

The Winterhaven Project marked a bold rebranding of electrogravitic concepts into viable, testable technologies. With improved materials, aerodynamics, and voltage systems, Brown pushed electrokinetics into the realm of serious military interest. His patents from this era reveal a deep understanding of both engineering and physics and hint at potential that’s only now being revisited.

Could it be that the real leap forward in energy and propulsion is hiding in the past?

Where Curiosity Turns into Breakthrough

The most remarkable discoveries begin with a question, a conversation, or a spark. Townsend Brown didn’t wait for approval; he followed the science wherever it led, and in doing so, he invited others to imagine more.

If you’re experimenting with motion-based energy, exploring boundary-pushing ideas, or simply drawn to technologies that challenge convention, I’d love to hear about it. Insight grows when minds connect, and the next big leap might begin with the conversation we start today.

Let’s keep the momentum alive. Connect with me on LinkedIn and share what you’re exploring. You can also email me at👉 letstalk@larrydeavenport.com .

After all, the future isn’t written in laboratories alone. It’s written in the conversations that spark new ideas.

About the Author

Larry Deavenport is a researcher, speaker, and educator with more than 40 years of experience exploring the frontier of electrokinetics, which he calls energy in motion. As founder of Deavenport Technology, he is dedicated to equipping innovators, researchers, and engineers with the clarity, tools, and mentorship they need to transform scattered theories into working prototypes.

Larry’s work focuses on bridging the gap between curiosity-driven experimentation and practical application. His teaching combines structured principles, hands-on demonstrations, and one-on-one guidance to help learners refine breakthroughs and accelerate discoveries. Through his keynotes, workshops, mentoring programs, and his two signature master courses, Larry inspires a new generation of pioneers to explore advanced gravitics and motion-based energy systems that align with natural forces and reduce environmental impact.

Passionate about both discovery and education, Larry continues to share his research and insights at conferences, in collaborative forums, and through his growing platform at Deavenport Technology. His mission is to guide bold thinkers who are ready to move from possibility into progress, shaping the future of sustainable energy and redefining what is possible.

References

- U.S. Patent 2,949,550

- U.S. Patent 3,022,430

- Avrocar Project – National Museum of the USAF

- Tesla Tech Conference – Extraordinary Science Events